more>>More News

- National Day

- ways to integrate into Chinese style life

- Should they be in the same university with me?!!

- Chinese Ping Pang Legend: the Sun Will Never Set

- A Glance of those Funny University Associations

- mahjong----The game of a brand new sexy

- Magpie Festival

- Park Shares Zongzi for Dragon Boat Festival

- Yue Fei —— Great Hero

- Mei Lanfang——Master of Peking Opera

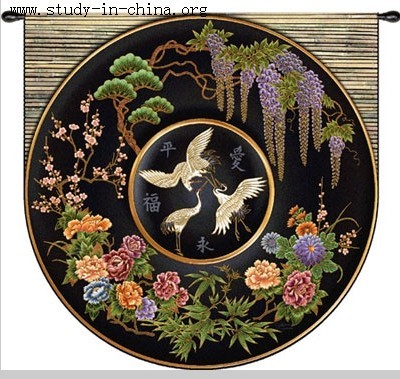

Chinese Cloisonne

By admin on 2015-02-03

Chinese cloisonné was strictly of the enameled variety (the other, and original, variety used small, worked precious stone pieces that were held in place by the soldered metal strip that was snuggled around the stone's base, similar to the way that modern-day jewels are held in their settings), and as such was most certainly an imported craft. The earliest cloisonné seems to have originated in Egypt around BC1800. The earliest cloisonné was, as indicated, small pieces of precious stone that were set onto a copper base onto which brass strips, standing edgewise, had been soldered, creating small enclosures, or cloisons, in French. The brass enclosures were intended to be seen, in much the same way that the lead "enclosures" of stained-glass windows were intended to be seen.

In time, artisans developed a powdered stone material that could be filled into the enclosures, then fired, producing a flat, smooth surface, and this of course made it possible to create entire mosaics of varying colors. Later still, during the 8th century, Byzantine cloisonné craftsmen began to use fine copper wire, or filigree, and this paved the way for the most delicate, most detailed cloisonné work. Cloisonné of the type produced in China, i.e., made by firing powered stone material into a durable enamel, was often referred to as "enamelware".

It is widely accepted that the most exquisite enamelware ever produced stemmed from China, which is claimed by some to have produced its first enamelware during the Yuan (1279-1368) Dynasty, though the earliest historically established (carbon dated) exemplar of Chinese cloisonné stems from the Ming (1368-1644) Dynasty reign (1425-35) of Emperor Xuande. However, the enamelware of this period exhibits such refined technique that it suggests years of prior experience, which lends credence to the claim regarding the Yuan Dynasty origin of enamelware in China. Moreover, cloisonné was described in the book, Ge gu yao lun ("Essential Criteria of Antiquities"), published in 1388 by Cao Zhao, where it was referred to as dashi ("Muslim") ware, perhaps a reference to the fact that cloisonné originated in Egypt, which, by then, was a Muslim country.

Chinese cloisonné had long since become a Silk Road commodity (traveling to China initially, then later from China to India, the Middle East and Europe) by the time of the Ming Dynasty reign (1449-1457) of Emperor Zhu Qiyu, more commonly known as the Jingtai Emperor, the period during which Chinese cloisonné became most famous.

There is a story, not lacking in plausibility, that suggests that after the fall of the Byzantine Empire, i.e., after the fall of Constantinople, the "goldsmiths" of the city, not being able to flee toward western Europe as they would have run directly into the unwelcoming arms of the city's besiegers (i.e., the Turks under the command of Mehmet II), fled instead eastward along the Silk Road route and ended up in China, where they – of course! – made "enamelware"!!

Note that Constantinople fell in 1453, and China's best enamelware, known as jingtailan ("Jingtai blue ware"), a reference to the reigning Jingtai Emperor and the fact that blue was apparently the favorite cloissonné color in China at the time (not the favorite handicraft color, nor the favorite color of the court of Emperor Jingtai, just the favorite cloissonné color, for some unexplained reason), was produced some time between 1449-1457.

- Contact Us

-

Tel:

0086-571-88165708

0086-571-88165512E-mail:

admission@cuecc.com

- About Us

- Who We Are What we do Why CUECC How to Apply

- Address

- Study in China TESOL in China

Hangzhou Jiaoyu Science and Technology Co.LTD.

Copyright 2003-2024, All rights reserved

Chinese

Chinese

English

English

Korean

Korean

Japanese

Japanese

French

French

Russian

Russian

Vietnamese

Vietnamese